As I was reading it, I found it a little kitschy and a a little hard to follow, feeling like I knew I'd have to reread it if I wanted to truly understand. After I finished the book, I read a bunch of reviews and most people described the chapters as more like short stories. Had I gone into the reading with that mindset, I think it would have been a different experience.

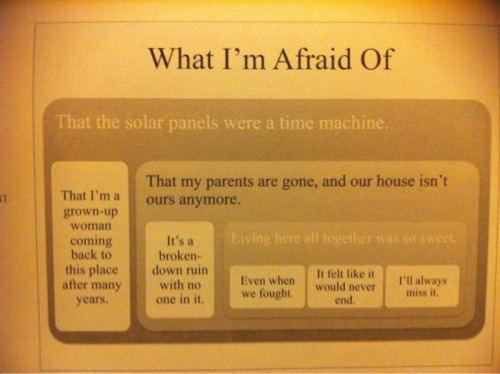

The part of the book that I loved, however, was when the narrator was Sasha's 11 year old daughter Alison, who told her story in a powerpoint journal. The future sections of the book all showed technology gone incredibly annoying, but somehow this was a thought provoking blend of the visual and the written. A few of the things she mentioned particularly struck a chord with me and I found a bit of a kindred spirit in both of these female characters. This is, in part, a book about time, and these moments felt the least jaded and most hopeful to me.

The "What I'm Afraid Of" slide came after she had gone on the kind of long walk with her dad where the world seems incredibly far away. This is what she is thinking as she walks back to their house.

|

| page 299 |

My heart hurt in a way I can't describe when I read this. I remember having moments like this when I was little, but not having a way to express it: feeling, as a child that I would long for the moment I was standing in later as an adult, and feeling despair for the fact that it was impossible to hold on to it. Alison's voice as a character is different from the rest of the characters, possibly because she is youngest of all narrators, and possibly because what she imagines missing is so pure. The other narrators, when they are older, miss the teenage and young adult years: the freedom and the hope of what it yet to come.

"Mom's Art" slide is where Alison tries to explain the art that her mom, Sasha (who the reader meets at the beginning of the book as a 30 year old women in therapy for kleptomania):

"She uses found objects, they come from our house and our lives, she glues them onto boards and shellacs them, she says they're precious because they're casual and meaningless, but they tell the whole story if you really look."

This is an interesting fact to learn about Sasha: that she now "steals" objects that have no meaning to most people, but is able to find meaning in them, and that she seems able to create true meaning in her life. As a reader, writer and sometimes poet, I love small details that feel meaningless to most people, but have a story underneath. I think it's significant that Egan uses the word shellacs--it sounds a bit like a desperate push to save something, or, an artistic way to create and remember the details that get forgotten among louder, bolder ones.

I've found myself telling others recently that maybe New York has finally gotten to me because I have felt really cynical about a lot of things lately. This is not how I would ordinarily describe myself, so it has been interesting to find this creeping in on my psyche and seeing it play out in my life. Reading this section reminded me that I am both nostalgic and sentimental; and rather than seeing those characteristics as sappy or weak, I think that they allow me to look at the big picture of beauty in life--and that is just what this part-time, temporary cynic needs.