My blog is about to celebrate its 5th anniversary next month. I wrote my

first post on January 6th, 2007, partly to slow down and think about what I was reading again and partly in an effort to get more comfortable with sharing my writing in a "public" space (I would like to thank my 4 loyal readers at this time: Mom, Dad, Alison Covey, Kendra Bloom). Every year when I'm home for Christmas I read every post I wrote over the year and choose the top ten best books I've read.

Usually, it takes me many hours to reread my blog posts for the year. As I read, I take notes and end up with a list at least 20 contenders for

the coveted top ten. I have to do some serious thinking and rereading of posts to decide which books had the biggest impact on my thought life--and then spend some serious time laughing about the nerdy ways I spend my time. This year was not so difficult. Sadly, I don't think I can attribute that to any increased coolness to my life, but I do think I have a few answers/self justifications for the reasons why this year I had only 23 posts (2008 holds the all-time high of 97):

- The spring was filled with YA books that enriched my teaching life and a side project I'm working on, but weren't necessarily significant enough for me to subject my loyal readers (see above) to.

- The summer, normally the two months that I read the highest number of books, was filled with Infinite Jest, a book that I felt I needed to finish before I posted anything about it. (Then, the fall happened and I still have 5 additional posts about Infinite Jest sitting in my drafts.)

- This fall, I got caught up reading books for and with my students. Many of my Saturday mornings, normally my drink-a-hot-beverage-and-write-about-my-reading time, were filled with training for my half marathon. Also, my book club choice was For Whom the Bell Tolls by Hemingway, which is not a read-before-you-fall-asleep kind of book: I would make it literally 3 pages and fall asleep. I'm finally about to finish it, which I owe to traveling 3 out of the last 5 weekends on U.S. Airways, who does not offer in-flight television.

All that to say, it is interesting to look back on a year through the lens of reading. I am nerdily excited for what 2012 will bring in my reading life...and the reflections that accompany good books. As for the Top Ten, I have to credit

Margaret, who is the sole other member of my

book club, because six of our choices made the top ten list this year. So, in no particular order:

The Hours by Michael Cunningham/

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (rereads)

These books have to be paired together and were two of the most thought provoking reads of the year.

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen

This book received an insane amount of press when it was published last year. Overall, especially because my book club read read

The Corrections first, I throughly enjoyed getting inside the mind of Franzen.

Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteygart

Not especially well written, but it definitely was the instigator of many great conversations and some science-fiction/technology induced nightmares.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

I think this was the most historically significant, jarring book that I read this year, and combined with its lyrical prose, it left me speechless.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby

Short. Beautiful. Inspiring.

Bossypants by Tina Fey

The most enjoyable book of the year.

Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

Harder than my book club's

run with the Russians a few years ago and encompassing almost all of my summer, this book was well worth it.

A Million Miles in a Thousand Years by Donald Miller (reread)

This book was a non-fiction, good reminder of all things I love about story and life.

The Summer Book by Tove Janssen(reread)

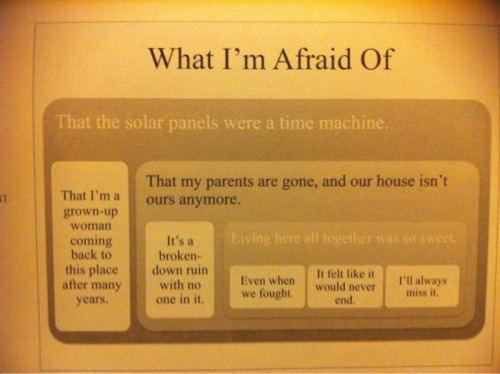

This book has become one of my yearly rereads and I've written about it

a few times. I spend the quiet, early summer mornings I have at my parents' house on their screened in porch reading just a chapter or two a day so that I can savor and soak in it during my entire visit. This year it was my respite from Infinite Jest, to make sure that reading was not only speaking into the my academically-minded side of my brain, but also my soul.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

I read the first book of this series as soon as it came out, on recommendation of our Teachers College professional developer. I never finished the series because I felt like I knew enough to talk about it with kids and had so many other books to read. However, after the Epic-Literary-Reread book club on

Harry Potter with my students last year, I thought that it would be cool to do the same thing with

The Hunger Games this year. I read these books in about a week and was amazed to see all of the entry points for young readers to have uber literary conversations. I have also been amazed at how many of my adult friends have been reading the series and are eager to discuss. A post-movie discussion party is in the works.

Cheers to reading and a 2012 filled with more writing about it!